In December 1940, the Luftwaffe dropped thousands of high-explosive bombs on Manchester, leading to hundreds dead and wounded, and the city’s architectural landscape forever altered. Manchester was once the industrial heartland of Great Britain, producing cotton and coal, but in those terrible years, the city became a battlefield: its factories closed, churches destroyed, and architecture scarred by war. Read more at manchester-future.

The 1940s were a dark chapter for the city. Manchester literally had to rise from the ashes. The process of restoring the city’s architectural appearance was incredibly long. Many iconic architectural landmarks were permanently destroyed and beyond repair. Therefore, new, more modern urban development projects had to be developed. This marked not just urban regeneration but a transformation. Manchester didn’t simply restore what’s lost; it evolved.

The Most Extensive Destruction

The most extensive destruction in Manchester occurred on the night of 22-23 December 1940. This night was also known as the “Manchester Blitz.” German bombers dropped over 450 tonnes of explosives and thousands of incendiary bombs on the city. Iconic landmarks such as Manchester Cathedral, the Free Trade Hall, and the Royal Exchange were severely damaged. Entire areas of Salford and Hulme were reduced to rubble.

It’s worth noting that during the war years, Manchester’s industrial sector was reconfigured to meet military needs. The city became a vital centre for wartime production. Its factories produced aircraft components, engineering products, and textiles essential for military requirements. This is precisely why it became target number one for the Germans.

Over 680 people died, thousands were injured, and more than 8,000 homes became uninhabitable. Manchester literally lay in ruins.

Architectural Projects for a New Manchester

The end of the Second World War brought not only peace and recovery to Manchester but also a moment of urban planning re-evaluation. Local authorities realised that the war had destroyed a significant part of the city centre, and returning to the former “magnificent” architecture was not an option. So, they decided to seize the opportunity for radical change.

Streets in old Manchester were narrow, designed for carts, not cars. Many buildings were old and cramped, lacking basic amenities. Water and electricity supply, sewerage, and the transport system – all remained at a pre-industrial era level. The city was growing and changing rapidly, and the infrastructure couldn’t keep up.

After the war, authorities decided not just to rebuild Manchester but to reinvent it. The city was to become modern, convenient, and spacious. Ambitious modernisation plans were developed: wide streets, new housing estates, green areas, and a modern transport network. A large-scale clearance of ruins and the construction of new quarters began, inspired by the ideas of modernism and functionalism. The city looked to the future – with new forms, technologies, and the goal of recovery.

Ambitious reconstruction projects fell on the shoulders of city planners and architects, as well as the Manchester Corporation. Inspired by the modernist ideas prevalent throughout Europe at that time, architects decided to implement bold and practical designs. The main goal was convenience, cleanliness, and ease of movement. The new “city of the future” was not meant to resemble the old Manchester.

Municipal estates, similar to Wythenshawe, whose construction began before the war, rapidly expanded. These suburbs were primarily intended to relieve pressure on the city centre and provide better living conditions. New water supply systems, gardens, and green spaces were planned there. By the 1950s and 1960s, multi-storey buildings and low-rise residential complexes began to replace inner-city slums.

New development was more than just architecture. It was social engineering – a vision of a better, more equitable post-war society.

Manchester’s Post-War Architectural Style

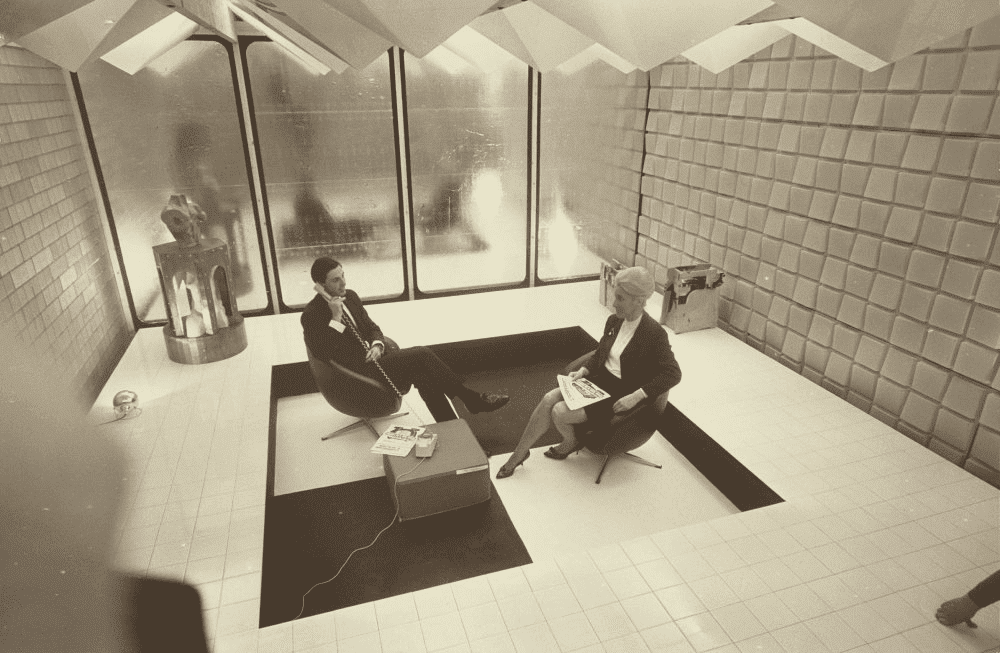

In the following decades, Manchester embraced modernism, and with it, Brutalist architecture. Rough concrete, geometric forms, and an emphasis on functionality rather than elegance largely defined post-war development. Buildings like the Arndale Centre (opened in 1975) and the CIS Tower (1962) were reflections of that era. Other projects included mass housing in areas like Hulme and Wythenshawe, where modernist estates were built according to “garden city” principles, with segregated transport, green spaces, and social infrastructure.

Modernism in that era was more than just an architectural style. It was a profound idea, a philosophy that rejected excessive ornamentation and focused on functionality and logic. After the war, the city desired simplicity and stability, and modernism provided that. It was a departure from the cramped, darkened, multi-occupancy Victorian buildings. Architecture was to become utilitarian, accessible, and modern.

Despite good intentions, not everything about modernism was perfect. In the 1970s and 1980s, many modernist estates were criticised for appearing cold, soulless, and unsafe. However, the problem wasn’t solely with the architecture but also with underfunding and complex social conditions.

Brutalism was also often criticised for its bleak appearance and overly large scale, though it accurately conveyed Manchester’s character. Such buildings were constructed to be “serious and long-lasting.” Furthermore, after the war, they symbolised strength, resilience, and the ability to endure anything.

At the same time, the restoration of cultural and historical buildings damaged during the German bombing began. Manchester Cathedral, severely damaged during the 1940 air raids, was restored very slowly but meticulously. It underwent restoration for decades. The combination of old and new Gothic stone and raw concrete in the cathedral became a distinguishing feature of post-war Manchester.

Urban Revival

By the end of the 20th century, Manchester’s architectural revival was still ongoing. It’s worth noting that in 1996, the IRA carried out a terrorist attack in Manchester. No lives were lost, but the city’s architectural appearance was once again damaged, leading to another series of reconstructions. In the 1990s, new architectural projects included modern glass buildings rather than concrete structures.

The post-war reconstruction laid the foundation for the city’s architectural character. A new Manchester emerged, where remnants of the industrial past and magnificent buildings were combined with innovative projects of the future – futuristic concrete buildings and multi-functional glass skyscrapers. New constructions completely transformed the city’s architectural landscape.

It’s worth noting that remnants of the former era still remained in post-war Manchester. These included old factories, mills, and plants. For some time, they stood abandoned, but the city authorities breathed new life into them, transforming them into creative hubs, restaurants, and residential complexes.

Even in the 2020s, Manchester retains traces of the Second World War – not only in the form of monuments or ruined buildings but also in the character of the city itself. The war changed the architecture, but even more so, the people. They knew how to persevere, how to rebuild, and did not let tragedies define them.

Manchester revived after the severe consequences of the Second World War. It became different – stronger, more modern, more vibrant. The war left its mark but did not break it.

- https://ftanda.co.uk/thoughts/edwardian-classical-architecture-in-manchester/

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/mmuvisualresources/albums/72157625953126198/

- https://www.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/british-post-war-architecture-modernism-futurism

- https://confidentials.com/manchester/the-10-best-buildings-brutalist-manchester

- https://www.manchesterhive.com/display/9781526154996/9781526154996.00006.xml