Manchester is a city with a rich industrial and working-class past. It was a cradle for revolutions in manufacturing and ways of life. Dense buildings, factory chimneys, and narrow streets defined the environment that shaped the culture of Mancunians. The history of its social housing is a story of challenges and the pursuit of a dignified life. From the dark, cramped cottages built at the frantic pace of industrialisation to modernist high-rises, the architecture of workers’ housing reveals more about Manchester than any guidebook. More at manchester-future.

Industrialisation and the Housing Boom

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Manchester rapidly transformed into the industrial heart of Great Britain. The city was a whirlwind of construction, with textile mills, iron foundries, and engineering works appearing one after another. The economy demanded an ever-increasing supply of labour, which became the main catalyst for a demographic explosion.

As Manchester experienced this boom, the harsh realities of daily life for thousands of working-class families lurked behind the industrial progress.

A typical worker’s house from that period was a three-storey building with a cellar and an attic. Long windows on the upper floors allowed light into workshops, which were often located under the roof. Such buildings can still be seen today in historic areas like the Northern Quarter and Castlefield.

However, the sharp rise in population quickly led to a housing shortage. Demand outstripped supply, and landowners began selling off plots on the outskirts of the city to speculators. These speculators, in turn, divided the land into narrow strips and sold them on to small-scale builders. This is how new districts were born—chaotically, without a plan, and without infrastructure.

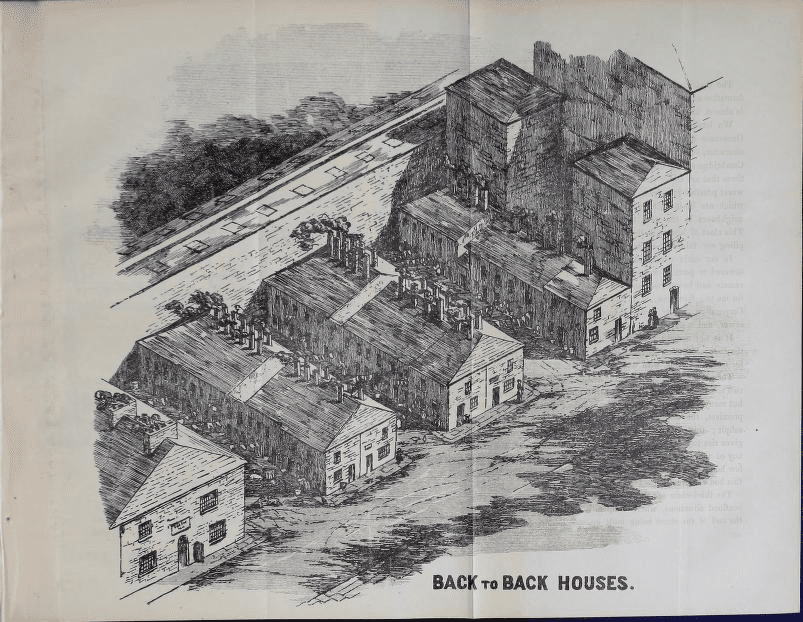

Most of the new homes were not built by factory owners, but by private investors whose sole focus was profit. This meant that development proceeded without any overall urban plan: streets were misaligned, and houses were built at odd angles, often crammed right next to each other. This gave rise to the typical “back-to-back” style of housing.

Cellars were rented out separately, usually to the poorest members of society. These living spaces were accessed either by a narrow staircase from the street or through a hatch in the pavement. They were dark, damp rooms with no access to fresh air or sunlight.

As Manchester continued to grow rapidly, its physical area remained almost unchanged. To accommodate everyone, the building density increased: new houses were squeezed between old ones, and existing buildings were divided into sections to rent out every square metre. This resulted in appalling overcrowding.

By 1845, Manchester had reached its limit. In areas like Ancoats, Angel Meadow, and Lower Deansgate, true slums had emerged. The lack of sanitation, water, and ventilation made these places hazardous to live in. Disease, filth, poverty, and high mortality rates became an inseparable part of city life. Despite its status as one of the world’s great cities, Manchester had also become one of its most deprived—especially for those who built its wealth with their own hands.

Manchester became the world’s first industrial metropolis. But this economic ascent came at a heavy price: a vast gap between the rich and the poor, unsanitary conditions, a lack of infrastructure, and systemic poverty. Yet, it was through these trials that the city journeyed from a market town to a global industrial capital.

From ‘Back-to-Backs’ to Two-Storey Terraces: The Evolution of Typical Housing

The first houses for workers, known as “back-to-backs,” appeared in the mid-19th century. These were small brick houses built wall-to-wall, with no backyards and often no sanitation. Large families lived in these homes, sometimes all in a single room. Every inch of land was used as efficiently as possible, and privacy was a luxury. This housing was built quickly, cheaply, and with a single purpose: to put a roof over the heads of factory workers.

At the beginning of the 20th century, “terraced houses” emerged—rows of houses with a small front yard and a garden at the back. They offered better ventilation, separate toilets, and more light. After the Second World War, the government focused on solving the housing crisis. In the 1950s and 60s, two-storey blocks, built as part of a massive public housing programme, became common. These homes were constructed from concrete or brick, featured large windows, and shared courtyards, sometimes even with playgrounds. Their layouts were more considered, and living conditions were more comfortable.

Each stage of construction reflected the social changes and ambitions of its time. The shift from dark stone houses to bright, spacious flats marked a change not just in architecture, but in the very idea of a dignified life.

Ancoats – The World’s First Industrial Suburb

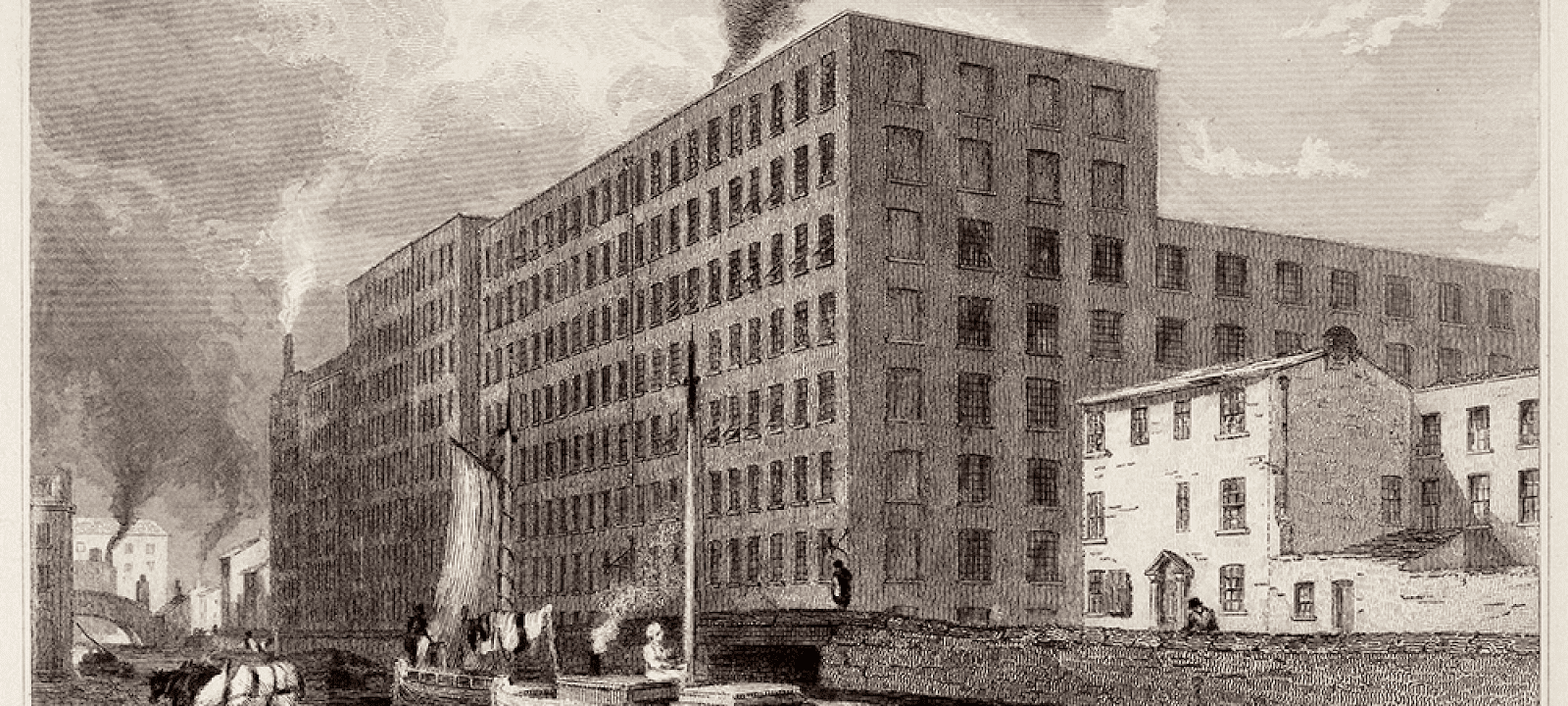

At the end of the 18th century, the Ancoats area of Manchester was typical countryside, covered with fields and pastures. Within just a few decades, however, the landscape changed beyond recognition. In the 1780s, textile mills, warehouses, and workers’ housing began to be rapidly constructed. By 1815, Ancoats had become one of Manchester’s most densely populated districts, with an incredible concentration of the city’s cotton mills.

Ancoats became the world’s first example of a residential development created specifically for the needs of the new urban working class. It was not just an industrial cluster, but a true industrial suburb where factories and homes existed side-by-side. This model became a blueprint for future industrial cities around the world.

Unfortunately, much of the area’s original housing has not survived. During the modernisation of the district in the 20th century, many buildings were demolished. Archaeological excavations, part of the East Manchester Regeneration scheme, have uncovered the remains of foundations, old floors, and everyday items belonging to the first residents of Ancoats. These findings have provided a deeper understanding of what life was like for workers during the period of intense industrial growth.

Today, Ancoats is experiencing a renaissance. Old industrial buildings are being converted into residential complexes, cafes, and creative spaces. The district is once again becoming a desirable place to be, not because of its factories, but because of its unique industrial charm, history, and cultural potential.

What Has Survived and What Has Vanished: The Fight for Architectural Heritage

Many of the early “back-to-back” houses have already disappeared from Manchester’s map. They were considered unsafe and obsolete, and were demolished en masse in the 1960s and 70s. However, some examples have been preserved, particularly in Ancoats, Hulme, and Ardwick. Today, they have listed status and offer a glimpse into the daily life and style of the working class of that era. At the same time, many others have been rebuilt or modernised beyond recognition.

Contemporary challenges involve not only preserving old buildings but also understanding their value. Some mid-20th-century housing, though appearing unremarkable, is a testament to the post-war boom and the belief in a new architecture for a better life. In the 2020s, these housing estates are either falling into disrepair or being transformed into expensive loft apartments.

Renovation or Redevelopment: A New Perspective on Old Housing

The city and its architects have repeatedly faced a dilemma: should they preserve the authenticity of historic social housing or sacrifice it for modern comfort? Renovation has become the most popular compromise. It allows the historic appearance of buildings to be maintained while modernising their internal systems, insulating facades, and updating interiors. This approach is popular in Manchester, Salford, and other towns in the county, where old “terraced houses” are being converted into modern, yet affordable, homes.

On the other hand, some areas are completely demolished to make way for new constructions. In the 21st century, these are often more expensive and unaffordable for the majority of the city’s residents. This draws criticism from urban planners and the community, as it disrupts the social fabric of neighbourhoods and causes the city to lose a part of its identity.

An alternative approach is “soft modernisation.” This involves adapting housing complexes to modern standards while retaining their character. For example, adding green spaces, converting cellars into community areas, or modernising roof structures. This path has been taken in areas like Moss Side and Cheetham Hill.

The Impact of Social Architecture on Manchester

While social housing in the past might have been all brick and concrete, things have changed in the 21st century. Today, it is about community, proximity, and mutual support. Architecture influences how people communicate, feel safe, and raise children. In the 2020s, new or modernised social housing with internal courtyards, open-plan entrances, and shared spaces is designed to encourage social connections. In contrast, closed-off or “corridor-style” developments often lead to isolation.

Therefore, the future of social housing in Manchester is not just about comfort and functionality, but also about nurturing the city’s spirit. With respect and care, its old working-class neighbourhoods can become models of sustainable living.

- https://archaeologicalresearchservices.com/uncovering-manchesters-industrial-past-part-4-workers-housing/

- https://www.julianwadden.co.uk/property-guides-and-resources/the-history-and-benefits-of-terraced-houses/

- https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8982378/brick-from-industrial-workers-housing