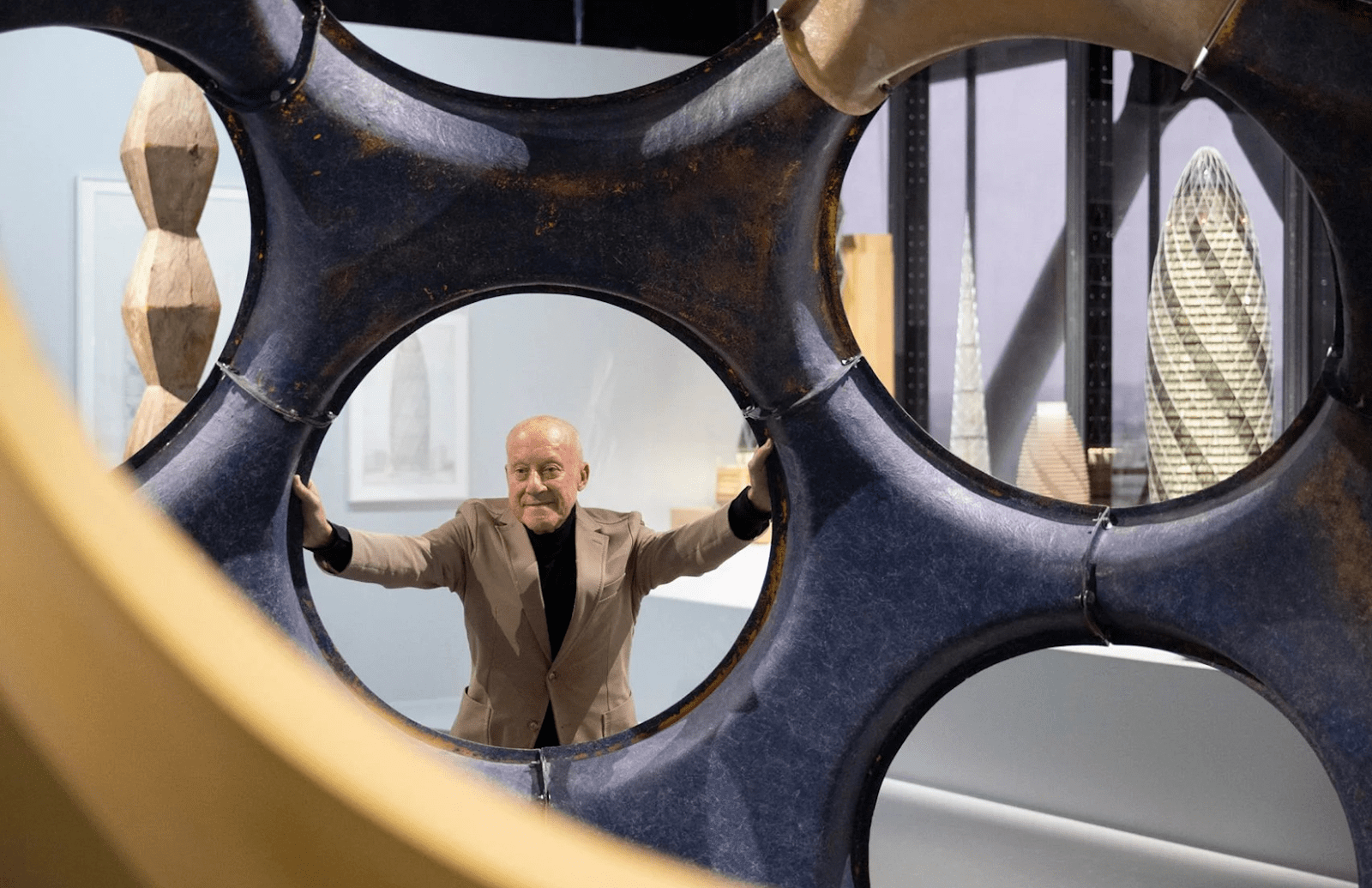

When it comes to the most influential architects in the world, the name Norman Foster always comes to mind. The creator of such global architectural legends as the “Gherkin” in London, the Millau Viaduct in France, and the “Apple Park” campus in California, Foster has become world-famous, changed the face of cities, and inspired thousands of architects. And his story began in Stockport, near Manchester. It was this place that shaped him into a future architectural genius. Read on for the story of Norman Foster’s development in this article from manchester-future.

Early Years in Manchester

Norman Foster was born in 1935 in Reddish, near Stockport, and grew up in a modest family in the Manchester suburb of Levenshulme. His father was a painter, and his mother worked in a bakery. His parents worked very hard, which set an example for the young Norman. He understood the importance of perseverance and discipline.

At school, however, Foster was very shy and withdrawn. Moreover, he was often bullied by his classmates. He frequently found solace in books and reading.

Foster began his working life early. At 16, he left school and started working as a clerk in Manchester Town Hall. After serving in the Royal Air Force, he took a job at an architectural firm, where he first felt he had found his calling. His drawings and designs quickly attracted attention, and he was promoted.

Despite a lack of financial support, Foster enrolled in the School of Architecture at the University of Manchester in 1956. He combined his studies with night shifts at a bakery, working as a bouncer, and selling ice cream. But his hard work was rewarded, and all his efforts were not in vain. In 1959, he received the Royal Institute of British Architects Silver Medal for a detailed architectural drawing of a windmill.

At that time, architecture in Manchester was a mix of pragmatism and burgeoning modernism. Post-war reconstruction had begun to move away from traditional forms. The city, scarred by bombings and a steep industrial decline, was in need of new ideas. This was an experience that would stay with Foster for his entire life.

After graduating from university, he received a prestigious scholarship to study at the Yale School of Architecture in the United States. There, he met Richard Rogers, his future collaborator. Influenced by Professor Vincent Scully, Foster and Rogers embarked on a journey across America to study architecture in practice. It was this trip that solidified his ambition to design buildings that would change cities.

The Path to Becoming a Legendary Global Architect

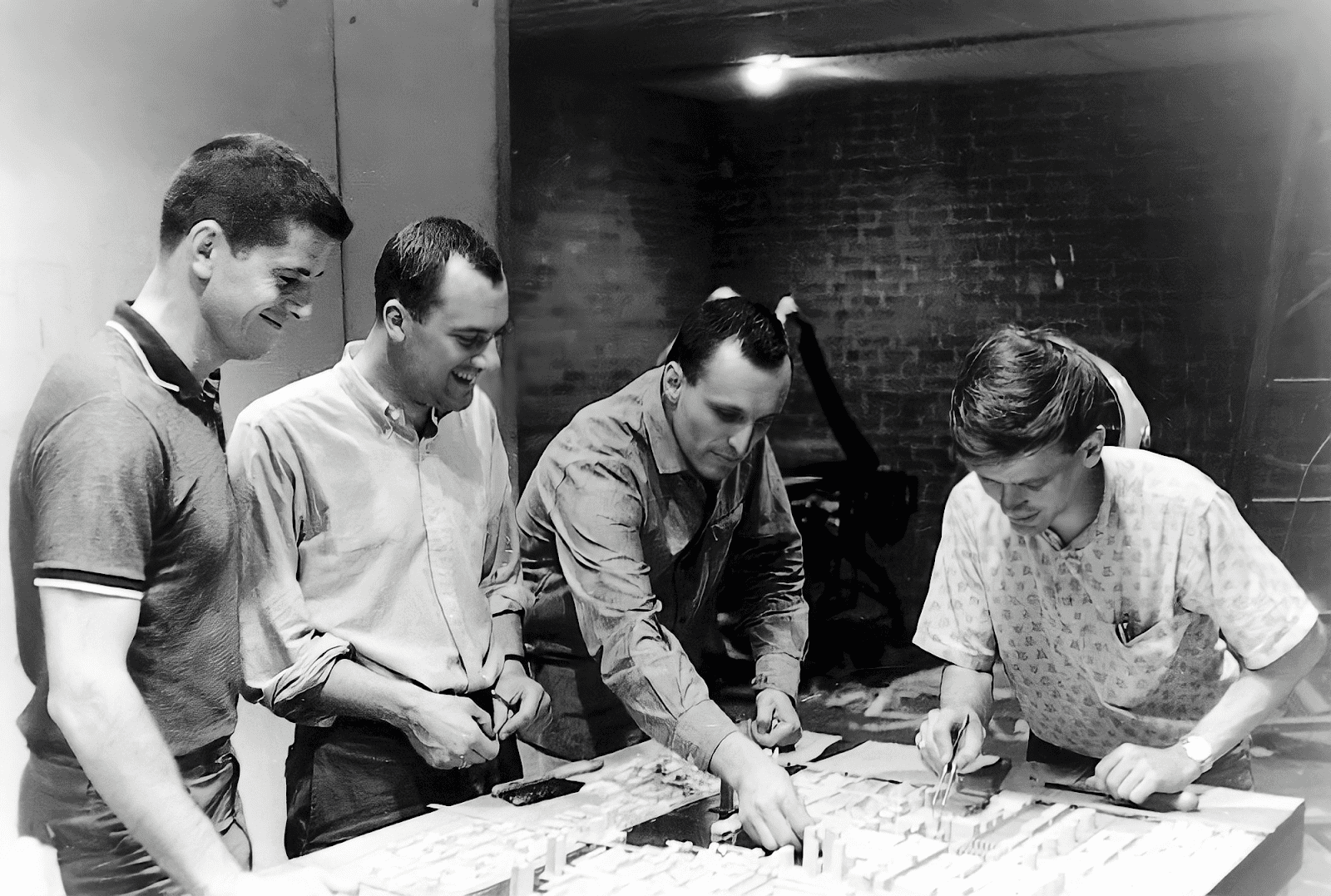

Although Foster was deeply impressed by the United States, he returned to his native Great Britain in 1963 and, together with Richard Rogers, Wendy Cheesman, and other partners, founded the architectural studio “Team 4”. One of their first projects was the futuristic glass pavilion, the “Cockpit,” in Cornwall. It was a minimalist structure with a profound vision of the future. It is worth noting that it was here that Foster’s unique architectural signature began to emerge. After “Team 4” disbanded in 1967, he and Wendy created “Foster Associates” – a firm that quickly became a leader in the architecture of a new era.

In the late 1960s, Foster collaborated with the innovator Richard Buckminster Fuller, which influenced his ecological approach to architecture. Together, they worked on a number of projects, including the Samuel Beckett Theatre at Oxford.

In its early years, “Foster Associates” specialised in industrial buildings, but everything changed in the 1970s. Among their key works was the headquarters for the Willis Faber & Dumas insurance company in Ipswich, completed in 1975. This was a revolutionary building with a glass facade, a rooftop garden, a swimming pool, and a gymnasium. It promoted the idea of an open-plan office and employee well-being long before it became a trend.

The Legends Foster Created

In 1978, Foster completed the project for the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich. It was one of his first major public projects. In 1981, he was entrusted with designing the new terminal for Stansted Airport. It should be noted that upon its opening in 1991, this project brought him international acclaim: the terminal became a model of high-tech architecture and received the prestigious Mies van der Rohe Award.

By the 1980s, Foster had established himself as a master of corporate architecture. He designed the HSBC headquarters in Hong Kong. It was an incredibly transparent building with a magnificent view of the harbour. At the time, it was one of the most expensive buildings in the world. Foster himself later admitted that without this contract, his firm might not have survived.

In the 1990s, Foster was commissioned to develop a project on the site of the destroyed Baltic Exchange in London. Initially, he proposed building the “Millennium Tower,” a skyscraper 385 metres high, but the project was not approved due to criticism of its height. In its place appeared the famous “Gherkin” – 30 St Mary Axe. The building’s shape became iconic, and its engineering solutions combined modern technology with natural principles, such as natural ventilation. In 1999, the studio was officially renamed “Foster + Partners”.

By then, Foster’s style had become more concise and contemporary, moving away from the characteristic “machine” high-tech of his early period. In 2004, he designed the tallest bridge in the world – the Millau Viaduct in France, which was described as a “work of art.”

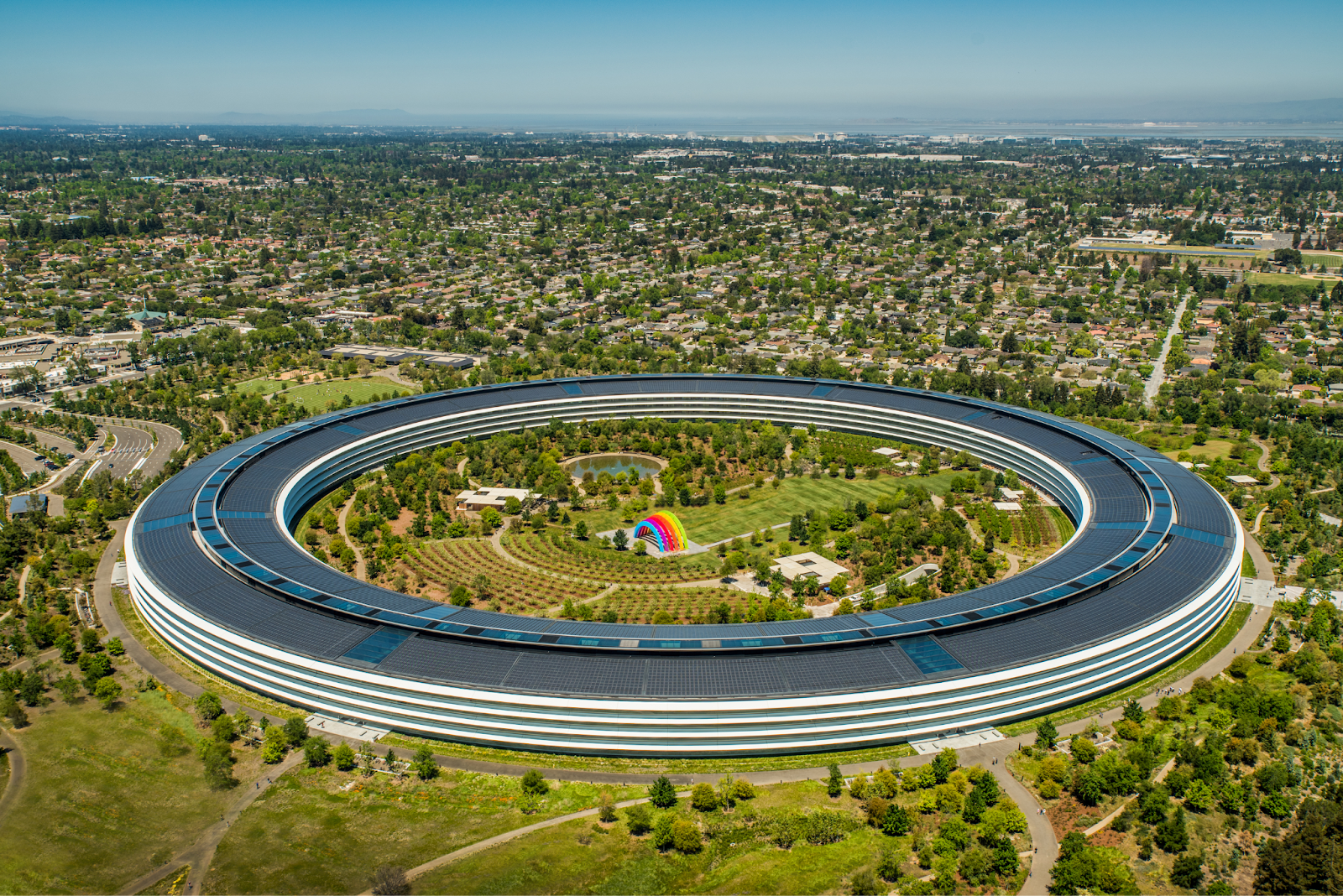

From 2009, Foster worked closely with Steve Jobs on the project for the new Apple campus. The circular “Apple Park” building in Cupertino was opened to employees in 2017, after Jobs’s death, but was realised according to his vision.

In 2007, rumours emerged of Foster’s desire to sell a stake in his company, estimated to be worth £300–£500 million. At the same time, he was working with Philippe Starck and Richard Branson on the “Virgin Galactic” project.

Foster is actively involved in social and educational projects, including the architectural charity “Article 25” and “The Architecture Foundation”. He emphasises the importance of involving young architects. The average age of his firm’s employees remains around 32.

In 2022, it was announced that Norman Foster would assist in the reconstruction of Ukraine. According to data from 2024, “Foster + Partners” earned over $500 million in fees, 40% of which came from clients in the Middle East.

Later Life and Recognition

In the 2000s, Norman Foster faced serious health problems. He was diagnosed with bowel cancer and told he had only a few weeks to live. However, the architect underwent a course of chemotherapy and made a full recovery. He later also suffered a heart attack. Despite this, Foster continued to work, remaining one of the most influential architects of his time.

Although Norman Foster has designed for presidents, billionaires, and cities around the world, he has always acknowledged his Manchester roots. He speaks of the city as a place that taught him how to solve problems, respect materials, and dream big. Manchester gave him a foundation, not just in architecture, but in life. It showed him how things are built, why they are important, and whom they serve.

In 2007, Norman Foster received the Lynn S. Beedle Lifetime Achievement Award from the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. He was later awarded the prestigious Aga Khan Award for Architecture for the Petronas University of Technology project in Malaysia. In 2008, he was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Dundee, and in 2009, the Prince of Asturias Award in the “Arts” category.

In 2012, the artist Sir Peter Blake included Foster in a modern version of the iconic album cover for “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” as one of the most inspirational figures in British culture. In 2017, Foster became a recipient of the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement, presented to him by Lord Jacob Rothschild.